Nothing divides Americans like the question of free speech: what does it mean, who deserves it and who doesn’t. Conservatives like to complain about being ‘censored’ or ‘cancelled’ for their attacks on LGBTQ rights or mask mandates, but they’ve recently started trying to impose all sorts of restrictions on speech in education , particularly on issues of gender identity, sexual orientation and race. .

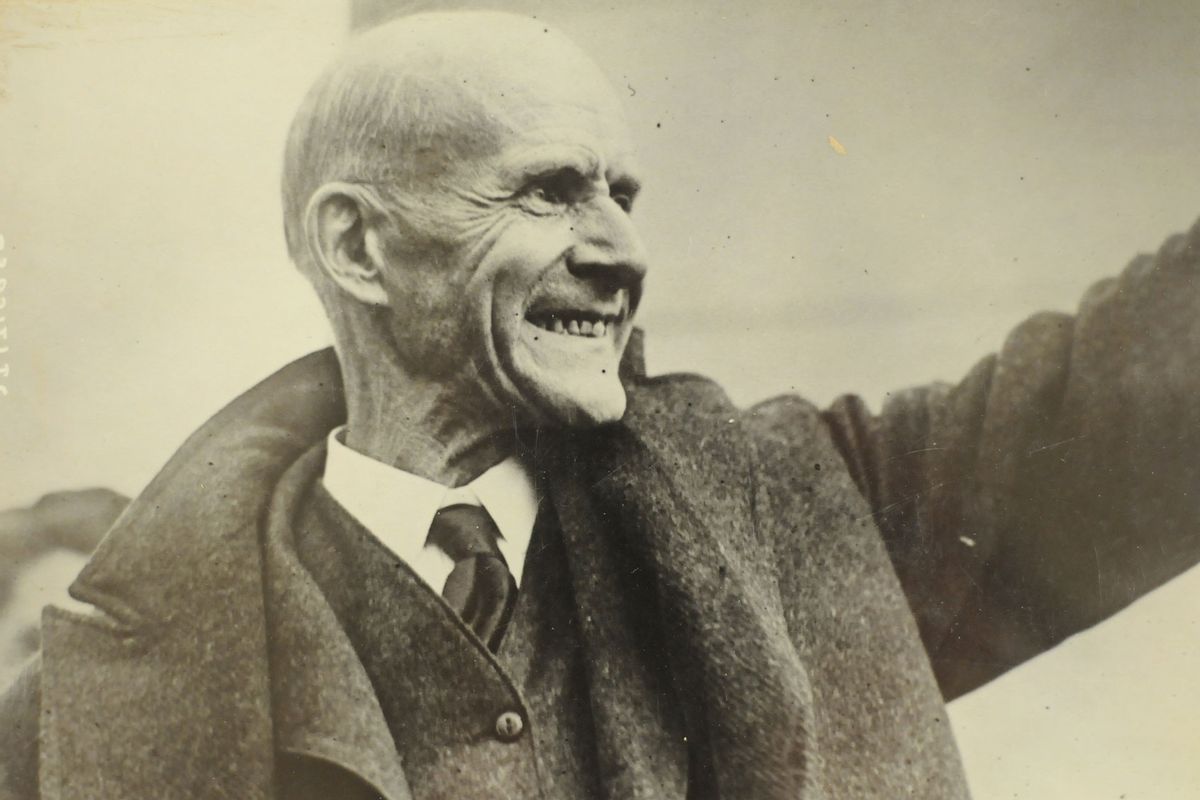

As for the legendary Eugene Victor Debs, however – a leading labor and political activist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – there is no doubt: he was a martyr for free speech. and a case study for overcoming oppression. When Debs was sent to prison for telling “the man” the truth – and in this case, it really was the man, i.e. President Woodrow Wilson – he fought back by deciding to run for president himself.

RELATED: We Celebrated ‘Free Speech’ This Week – Just When It Slips Away

Our story begins on June 16, 1918, on a balmy afternoon in Canton, Ohio, where Debs was scheduled to speak at the State Socialist Convention and then at a picnic — in fact, the one that bears her name. Debs was then a 62-year-old labor veteran, who helped found the American Railway Union (ARU) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and had gradually moved left from the Democratic Party to various socialist parties. organizations. In the 1900 presidential election, he was the presidential candidate of the Social Democratic Party; after that party’s implosion, he was the Socialist Party’s candidate in 1904, 1908, and 1912. Voter turnout in this last election was so low that although Debs received only about 900,000 votes, c was about 6% of the total – one of the most impressive electoral performances by a left-wing independent in American history. (Robert La Follette got 4.8 million votes and nearly 17% of the total in the 1924 election, along with his home state of Wisconsin; by contrast, Ralph Nader got nearly 2.9 million votes in the 2000 elections, but that was only 2.7% of the total.)

This election cemented Debs’ status as America’s most powerful celebrity and socialist, prominently articulating an anti-capitalist, anti-corporate ideology that would inspire generations to come (including Bernie Sanders, who took Debs as a model). In 1918, however, Debs was preoccupied with foreign policy. After considerable hesitation, the United States had committed troops to fight in World War I, which Debs said was driven by irrational nationalist rhetoric and a combination of imperialism and capitalism gone mad. (The term “military-industrial complex” was not yet in use, but Debs would surely have adopted it.) For him, the so-called Great War was about the suffering and death of the working class for the benefit of a wealthy few.

Want a daily recap of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Unsurprisingly, Debs was also opposed to the military plan, which put him at odds with the administration of Woodrow Wilson, which had just passed an infamous piece of legislation called the Espionage Act, which, among other things, made it a federal crime interference in conscription. When Debs spoke in Canton that June afternoon, the audience included Justice Department agents eager to see if they could trap him in something that could potentially violate the law. Debs was aware of the risk and warned his audience to be “extremely careful, careful about what I say, and even more careful and careful about how I say it.” Maybe he was daring the agents to prosecute him for everything he said, and they took the bait, as a federal prosecutor named Edwin Wertz did after Debs said this:

They have always taught you that it is your patriotic duty to go to war and slaughter yourselves under their orders. You never had a say in the war. The working class that makes the sacrifices, that sheds the blood, has never had a voice in declaring war.

As soon as he was charged under the Espionage Act, Debs knew he would be convicted. It was essentially a political show trial, an attempt by Wilson to bully left-wing critics into silence, in a climate of wartime patriotism where Americans were even more suspicious of the left. than usual. Debs declined to call any defense witnesses, speaking directly to the jury to explain why he didn’t want to play the court game. After his inevitable conviction, he delivered a statement to court which will later be immortalized:

Your Honor, years ago, I recognized my kinship with all living things, and decided I was no better than the baddest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that as long as there is a lower class, I am part of it, and as long as there is a criminal element, I am part of it, and as long as there is there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

I have listened to everything that has been said in this court in support and justification of this lawsuit, but my mind remains unchanged. I regard the Espionage Act as a despotic law in flagrant contradiction with democratic principles and with the spirit of free institutions…

Debs’ campaign in 1920 was not so much about what he said or did as about the symbolic importance of “prisoner 9653” running for president.

The day Debs went to jail, a protest march in Cleveland was attacked by police, leading to the May Day riots of 1919. The Socialist Party once again nominated him for president, though that he didn’t show up in 1916 and probably didn’t It was expected in 1920. Debs wrote numerous statements from his prison cell, detailing his views on everything from the war to class inequality . But his campaign was not based on what he said or did, but on the symbolic importance of the imprisoned freethinker running for the highest office in the land. Fans didn’t just ask people to vote for Debs; they told them to vote for “Prisoner 9653”. Word quickly spread that Debs, evidently a kind and courteous man in his personal interactions, was very popular among prison staff and fellow inmates.

Of course, Debs didn’t win – he was running as a third-party candidate, after all – but he received just over 913,000 votes, slightly more than he had in 1912. Notably, that accounted for only about half of the total popular vote. vote (3.4%) as it had been eight years earlier, largely because the electorate was much larger: the 1920 election was the first in which all American women had the right to vote, after the passage of the 19th amendment.

This was Eugene Debs’ last presidential campaign. He declined to run in 1924, facing failing health, and died in 1926. If it had been Wilson, Debs might have died in prison – but it was the next president, conservative Republican Warren G. Harding (winner of that 1920 election), who finally let him go. After taking office, Harding sent Attorney General Harry Daugherty to discuss the terms of a possible pardon or leniency with Debs. On Christmas Eve 1921, Harding announced that he was going commute the sentences of 24 political prisoners of the Wilson era, and that Debs would be among them.

Harding made a point of criticizing Debs in his public statement, saying he was guilty of the conviction and calling him “a dangerous man calculated to mislead the thoughtless and offering an excuse to those with criminal intent.” Harding said he was granting clemency because of Debs’ age and physical frailty, and because he “was by no means as rabid and outspoken in his expressions as many others, and without his notoriety and the resulting far-reaching effect of his words, most likely, might not have received the punishment he did.”

As Debs left Atlanta Penitentiary on Christmas Day 1921, he and his brother heard hundreds of prisoners standing at the bars of their cells cheering him on. Harding then requested a private meeting with Debs – no reporters allowed – where he allegedly said to her, “Well, I’ve heard so much about you, Mr. Debs, that I’m now happy to meet you personally.”

There are many lessons to be learned from Debs’ story, but perhaps the most important is so obvious that it needs to be stated directly. When we talk about freedom of expression, there is a big difference between people who are simply criticized for what they say and those who are actually persecuted or oppressed for it. If people write mean things about your Netflix special, or if an online platform decides not to host a particular video, that’s not oppression or censorship. But journalists targeted for violence because of their reporting, or teachers who lose their jobs for telling the truth about American history, are truly oppressed, censored and silenced. Eugene Debs refused to shut up or follow the rules, and paid the price. That makes him a free speech hero, whether you agree with his views or not.

Read more from Matthew Rozsa on US history: